Centrelink's Net to Gross Earnings Calculator

What is this tool and why does the DSS use it to calculate debts? Is it legitimate or potentially unlawful?

The Net to Gross Earnings Calculator (N2GEC) is one of the many tools used by Centrelink to calculate debts alleged to be owed by welfare payment recipients to the Commonwealth. Others include the ADEX debt schedule explanation, the MultiCal tool, and the Casual Earnings Apportionment tool.

It appears that the N2GEC has only once been cited in an AAT2 decision relating to social security payments and debts. Even then, it was not discussed in any real detail. I will look at that decision below.

In essence, the N2GEC is a tool that the Department of Social Services and Centrelink (the Agency) use to calculate debt amounts in circumstances where only net records — such as bank statements — are available, and where employer records, for whatever reason, are unavailable or unreliable.

A consideration of the N2GEC is usefully guided by a journey through what appears to be the only case in which it has been mentioned.

Longford

In Longford1, the General Division of the Tribunal (AA2) noted that the AAT1 had remitted a Youth Allowance debt matter to the Agency for recalculation in accordance with directions. Those directions were quoted in the AA2 decision. In the original decision, the AAT1 had ordered the Agency to:

(a) adopt the actual earnings obtained from relevant bank statements provided by Ms Longford;

(b) apply the net to gross earnings calculator on the income received by Ms Longford during the relevant period, so no further verification is required from employers for the relevant period;

(c) consider each occasion Ms Longford notified of the income she received in the relevant period and the amount so reported with reference to the actual earnings from the bank account statements;

(d) recalculate the running balance of the income bank (or working credits) for the relevant period; and

(e) recalculate the amount of the overpayment of Youth Allowance paid to Ms Longford in the relevant period.2

The AAT2 decision in Longford does not disclose why the AAT1 member decided to remit the decision. Nor does the AAT2 decision disclose on what legal basis the decision was remitted. However, it is likely that the AAT has exercised its broad remittal powers pursuant to s 43(1)(c)(ii) of the AAT Act. Section 43(1) provides as follows:

(1) For the purpose of reviewing a decision, the Tribunal may exercise all the powers and discretions that are conferred by any relevant enactment on the person who made the decision and shall make a decision in writing:

(a) affirming the decision under review;

(b) varying the decision under review; or

(c) setting aside the decision under review and:

(i) making a decision in substitution for the decision so set aside; or

(ii) remitting the matter for reconsideration in accordance with any directions or recommendations of the Tribunal.

In Longford, the applicant had two debts. These debts were being appealed for the second time in the AAT2. They had already been appealed to the AAT1 and, at the end of that hearing, the applicant, Longford, was successful in obtaining directions from the member (the decision-maker), which directed the Agency to recalculate the debts. It is reasonable to infer that the evidence to support the debt amounts was not compelling or cogent enough to satisfy the member. Following that remittal, the applicant’s debts were recalculated. The first debt was reduced from $4,441.60 to $2,928.21 (a reduction of $1,531.39). The second was increased from $22,747.35 to $23,453.87 (an increase of $706.52). Overall, there was a reduction in the total debt amount of some $806.87 (from $27,188.95 to $26,382.08).

Although the specific facts and details of the applicant’s debt are not made clear in the AAT2 decision, that written decision reports that the applicant’s debt was subject to further recalculations following the use of the N2GEC. Presumably, the N2GEC had been used to calculate the debt amount by reference to the applicant’s bank statements. One would imagine this would enable a relatively accurate calculation of an individual’s income, provided the bank statements were accurate and complete.

Neverthless, the AAT2 decision reports that, once ‘the Agency obtain[ed] further bank statements and additional information from Ms Longford’s employers, the Agency again recalculated the alleged debts.’ Upon reciving that further information, the Agency then reduced the first debt to $0.00 and reduced the second debt by more than $6,000, from $23,453.87 to $17,241.43.

In respect of these recalculations, the decision is not clear. The member suggests that the additional information may have been determinative. However, the member also notes that the ‘debt period’ of the second debt was also reduced. Specifically, it was ‘reduced [to a] period of approximately 10 months from the previous calculation, which period was from March 2012 to June 2014’ (see para 21).

Although not a great deal can be said of this recalculation process, the Longford decision seems to suggest that some uses of the N2GEC by Centrelink will be inaccurate. Indeed, considering the significant recalculations that took place following the receipt by the Agency of further bank statements and employer information, how could the N2GEC be thought to be a reliable calculator?

Regretably, this is the only published decision in Australian history (to date) that makes passing reference to this internal tool. It is not prescribed by legislation, and no published guidance documents or working copies of the tool are available publicly.

When was the N2GEC established?

In February 2017, the Senate referred a matter to the Senate Community Affairs References Committee (Committee) for inquiry and report: namely, ‘The design, scope, cost-benefit analysis, contracts awarded and implementation associated with the Better Management of the Social Welfare System initiative.’ In its report, tabled 21 June 2017, the Committee noted the ways in which Centrelink had improved the Online compliance Intervention (OCI) process since the program was first trialled. The OCI process was later to be named in media reports, and to become well known, as the ‘robodebt’ program.3

In its evidence to the Commiteee in 2017, the Department of Human Services (the Department), as it then was, explained that one of those improvements was the possibility that Centrelink customers could now provide the Agency with bank statement to demonstrate their net income. The report notes the evidence of the Department as follows:

The main social welfare payments are calculated on gross payment, which would require people to have access to information from employers. If we use net income, people are able to use bank statements to say what actually went into their bank accounts in different periods, so that is an improvement there.4

Given this ability to provide bank statements is recorded as an ‘improvement,’ it seems likely that it was with this improvement that a tool would have been introduced to calculate debts from these newly permissable source of data — how else, after all, would this new record be converted into a feasible ‘proof point.’ Thus, it is likely the use of the N2GEC began some time in 2017, when the Agency began to consider, or even to rely on, bank statements to calculate gross debts: that is, to calculate an individual’s gross income from information recording their net income receipts.

Bank statements and the legislation

At this point, it is important to note that bank statements had been retrieved and used to investigate debts by the Agency and Department over a period that stretches much further back into history than 2017. Indeed, FOI files of customers indicate that Centrelink has used its powers under the ss 194 and 196 of the Social Security (Administration) Act 1999 (Cth) for many years, and at least as early as 2001. Section 194 relevantly provides that

The Secretary may require a person to give information, or produce a document, to the Department if the Secretary considers the information or document:

(a) would help the Department locate another person (the debtor ) who owes a debt to the Commonwealth under or as a result of the social security law; or

(b) is relevant to the debtor's financial situation.

It is possible, however (as has been suggested in private correspondence with me), that Centrelink did not, until the pilot of the OCI/robodebt program in 2015/16, use these bank statements to ‘calculate’ debts but rather only to ensure that no other sources of income were being hidden or concealed by the alleged debtor.

A few problems with the N2GEC

There are a few problems with the N2GEC. The first relates to its tendency to be misused, while the second is a more fundamental problem relating to its legitimacy as a calculator.

Uplift includes averaging

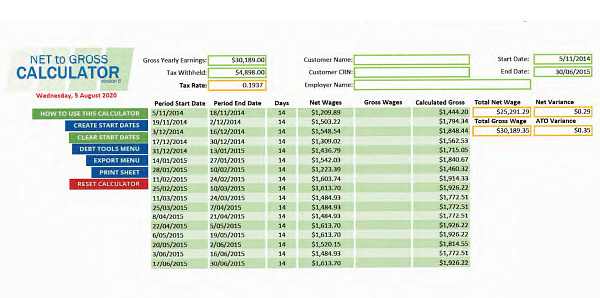

The first point has been raised, on Twitter, by NotMyDebt Support. That organisation has critcised the so-called ‘uplift’ process for using what is called ‘residual averaging of ATO PAYG match data.’ One of the relevant tweets, below, also includes an image of the N2GEC, which appears to be a software application similar to an MS Excel workbook:

The point advanced by the NotMyDebt Support relates to the way in which the N2GEC includes information received by Centrelink from the ATO — namely, tax annual withholding information — and, to the extent that it includes that information, also neccessarily includes ‘averaged’ data. In the above image, for instance, the entry in the ‘Tax Withheld’ cell is $4,898. This same amount also appears on the ‘Match Data (IRMD)’ record (produced by Centrelink) reproduced in the Tweet, below the N2GEC. Presumably, this amount of $4,898 has been sourced from the ATO matched date, and then has been inputted into the N2GEC calculator as one of the integers that is used to calculate the relevant taxation rate applicable to the fortnighly amounts. In this way, the taxation rate is itself an annual ‘average’ of the actually imposed (and inevitably variable) taxation witholding amount that was applied, fortnight to fortnight, by the employer. Centrelink has used the annual total of tax withholding to calculate an average tax rate, expressed as a percentage, and has then applied that tax rate, in reverse, to the net amounts actually recieved by the customer in their bank accounts.

This is an important point. It is important because it suggests that, unless the N2GEC is used only on bank statements, and strictly not on annual ATO data, it may still engage in averaging for the purpose of creating a debt that is not referable to or consistent with the actual gross (or net) income records.

The N2GEC is unlikely to use the actual tax withholdings

The second point is the same; but it is expressed in a more fundamental way. It is as follows. The N2GEC is almost certainly an erroneous way to calculate gross income amounts from net bank receipts. This is because it very likely does not use the actual withholding amounts that were applied to the customer’s income in respect of the period in which that income was earnt (weekly, fortnighly, monthly, etc.) and for each financial year in which it was earnt. But these actual withholding amounts are likely to be calculable and ascertainable, depending on the customer’s particular circumstances. This is because the ATO provides so-called ‘tax tables’ that prescribe the amount of tax that will be withheld by an employer who employs a taxpaying individual for almost every amount of income. The actual amounts in the tables increases by division of just two dollars: eg, 466, 468, 470, etc. The tax tables are issues in weekly, fortnightly and monthly versions, and they also provide for different kinds of employees: those who are casual workers, those who pay the Medicare levy, and so on. Once you ascertain the amount an employee was paid in net income, it is possible to find the relevant tax table applicable to that indivual and, based on the amount that was prescribed by the ATO to have been withheld, to reverse calculate the gross income in respect of that week, fortnight, or month.

Given that the ATO provide these detailed tax withholding prescriptions to employers in each and every financial year, the preferable way to calculate the gross income earned by an individual from their bank statements would be to use them. There is no need to create or employ the N2GEC. Clearly, the use of a N2GEC is both unneccessary and very likely to be inaccurate — especially for historical debts — because it is highly unlikely that the N2GEC does not make detailed adjustments for every single amount that is prescribed in the tax tables, or for every single year and income payment schedule provided for by the tax tables. Doing so would create an extremely complex piece of software.

It is most unlikely that the N2GEC accounts for the varying amounts of prescribed tax withholdings for each amount, and for each year, in its underlying algorithm. Instead, it is more likely that the N2GEC uses a flat tax rate, dependent on the amount inputted (such as, for instance, 20% tax will apply to a fortnighly net income of $500), to calculate the gross income. Of course, this is hypothetical. There is no way of knowing precisely how the N2GEC works without examining a copy of the software application’s code.

Insofar as the N2GEC does perform an operation equivalent to the one outlined above, however, it may be arguable that the N2GEC engages in a form of automated calculation that does not produce nor constitute legally sufficient evidence of an actual debt amount. In this regard, and strictly depending on the outcome of any examination of the tool, it may be arguable that, on the basis of the Amato ruling of the Federal Court of Australia, the use of the N2GEC to calculate a debt would, in the absence of direct employment information, amount to the production of information that is legally insufficient to raise the debt.

In other words, it is possible that the use of the N2GEC would be no substitute for the income records of the emmployee, such as their payslips. That is because, without those payslips, which record the actual gross income paid to the employee, it is likely that, in the words of her Honour Davies J, there would be no information before the decision-maker

capable of satisfying the decision-maker that:

(a) a debt was owed by the Applicant to the Respondent, within the scope of s 1222A(a) and s 1223(1) of the Social Security Act 1991 (Cth) in the amount of the reassessed alleged debt; or that

(b) any of the necessary preconditions for the addition of a 10% penalty to such a debt, as prescribed by s 1228B(1)(c) of the Social Security Act 1991 (Cth) were present.5

Longford and Secretary, Department of Social Services (Social services second review) [2020] AATA 5136 (18 December 2020) (Longford).

Longford, para 16.

Ibid, para 4.93.

See Amato v Cth (2019) Federal Court of Australia (VID611/2019), available at https://www.comcourts.gov.au/file/Federal/P/VID611/2019/3859485/event/30114114/document/1513665.