Welfare in Australia before 1908

The enactment of the Invalid and Old Age Pensions Act 1908 (Cth) ('IOPA') inaugurated welfare in Australia. But what came before it?

In my first post on Welfare law and MMT, I discussed the MMT position in relation to what a ‘successful economy’ looks like. I wrote a little about the creation of an aged welfare scheme in the United States in 1936 with the enactment, under Roosevelt, of the Social Security Act of 1935. I also alluded to the fact that Australia, at the federal level, became a welfare state in around 1946 with the constitutional amendment introducing the so-called benefits power, which allowed for

(xxiiiA) the provision of maternity allowances, widows’ pensions, child endowment, unemployment, pharmaceutical, sickness and hospital benefits, medical and dental services (but not so as to authorize any form of civil conscription), benefits to students and family allowances…

This was the start of the federal welfare state in Australia. Of course, welfare had existed in various forms within the continent before 1946.

As will be recalled by those familiar with the so-called Aborigines Welfare Board (AWB), created in 1940, ‘welfare’ existed in Australia well before 1946 — albeit at the state and territory level. Legislation such as the Aborigines Protection (Amendment) Act 1940 (NSW) established the AWB, which replaced the Aborigines Protection Board and was supposed to inaugurate a fresh and modern approach to Aboriginal welfare. But the AWB continued many of the Protection Board’s prejudicial policies towards children, policies involving the violent and paternalistic removal from families of these infants and adolescents, creating a ‘stolen generation’ of Indigenous children. The AWB was abolished in 1969 and, in its place, the Aborigines Welfare Directorate was established. At the same time, in NSW, responsibility for Aboriginal children was transferred to the state Department of Youth and Community Services.1

But before these mid-twentieth-century state-run programs of welfare were established, there was, in fact, a much earlier-established Commonwealth program of welfare for the elderly and the invalid — a program that was established in the same year in which the UK established its first welfare program for the elderely and invalid (in 1908) and well before the United States established its equivalent pension program in 1935. Following federation in 1901, a federal welfare program for the aged and invalid was one of the first orders of business for the new federal republic.

IOPA

Although Australia did not become a fully-fledged welfare state until 1946, the old age and invalid pension scheme originated only 7 years after federation, in 1908, when the newly formed Commonwealth Parliament passed the Invalid and Old Age Pensions Act 1908 (Cth) (IOPA).2 Section 15 provided that everyone of sixty-five years as well as everyone who had become permanently incapacitated for work and was sixty-five years would qualify, while in Australia, for an old-age pension. Section 15(2) allowed women of 60 years to attain the pension if so declared by the Governor-General. Conditions attached to the pension under section 17: for instance, s 17(c) required they must be ‘of good character’ while s 17(d) provided that, if the recipient be a husband, they had not deserted or neglected their wife without just cause. Further, s 17(e) was a means test, providing that no one who had accumulated property with a net capital value exceeding three-hundred and ten pounds (£310) would be eligible. Section 17(f) provided that a person who had indirectly or directly deprived themselves of property or income to render themselves eligible under s 17(e) would be ineligible.

NSW before the Commonwealth IOPA

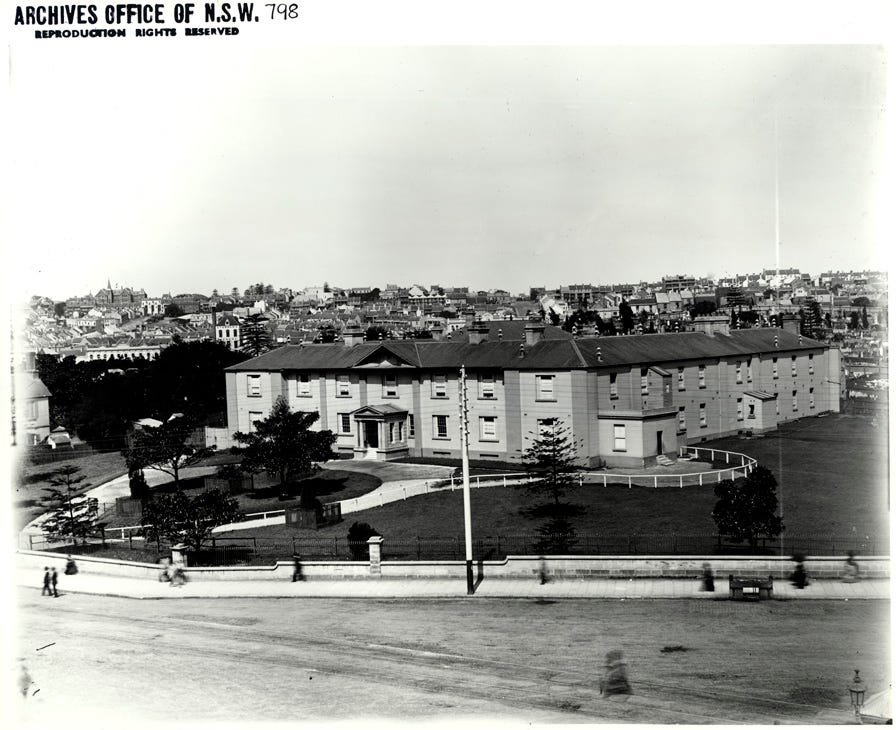

Prior to the enactment of the IOPA, the elderly or incapacitated received no financial support from the government, meaning that they required tending to by family, religious organisations, charities, or government asylums. In NSW, many of these ‘benevolent asylums’ existed, and in various forms. Before 1862, these asylums were totally independent of government (that is, the government of these colonies). One of these asylums was established by the Benevolent society, which was founded in 1813. It established the first asylum for the poor, blind and infirm in 1821 in Sydney, around where the Central railway Station sits today.3

In March 1862, a report authored by a Select Committee on the Benevolent Society — one of many such reports authored between 1830 and 1900 — found the Society's institutions were overcrowded and inadequate.4 In response to this report, the NSW colonial Government assumed responsibility for Society’s asylum, and established a ‘Government Asylums for the Infirm and Destitute Branch’ within the Colonial Secretary’s Department. This branch of the colonial government also administered asylums in other parts of the colony, including in Liverpool, Hyde Park Barracks and Parramatta. Control by colonial government of these asylums increased in the ensuing decades, until in the 1890s, when unemployment and poverty soared, resulting in an acute economic depression and strikes in the main streets of Sydney.5

Just before federation, the colony of New South Wales introduced legislation in 1900 for the provision of old-age pensions. The long title of the act was An Act to provide for Old-age Pensions, and for purposes in furtherance of or consequent on t h e aforesaid object (1900). Section 9 of the Act provided that every person in the community who

was above the age of 60 years

had resided in New South Wales for 15 years; and

whose income did not exceed £52 a year; and

fulfilled other criteria

would be entitled to a pension of ten shillings a week when single. Section 51, however, provided that the Act’s grant of an old-age pension would not apply to

(a) aliens; (b) naturalised subjects, except such as have been naturalised for the period of ten years next preceding the date on which they make their pension-claims; (c) Chinese or other Asiatics, whether naturalised or not; or (d) aboriginal natives.

Under section 11, married couples would receive nine pounds and ten shillings per year, diminished by various variables set out in that section.

Similar legislation was enacted in Victoria in the same year and, in 1908, an old-age pension Act was also enacted in Queensland. In 1908, New South Wales would also pass an Act to establish an invalid pension scheme.

The 1906 Royal Commission

In 1905, A Royal Commission had been convened to report on Old-Age Pensions, and its report was published in 1906.6 Between 1901 and the publication of that report, most other states, including NSW, Victoria and Queensland (as stated above), but also South Australia and Western Australia, took action to legislate for the benefit of pensioners and the elderly. When the Commonwealth scheme was established in 1908, however, all of these state schemes would be abolished.

While it was well-known that the new Constitution of 1901 empowered the Commonwealth to provide for invalid and old-age pensions under s 51 (xxiii), no legislation was to be enacted until 1908. It was some years coming. A Select Committee was appointed in 1904 to investigate the enshrinement of of old-age and invalid scheme, and this was converted into the Royal Commission in the following year. The commission consisted of 10 men, including chairman Sir Austin Chapman, a businessman and politician who was a partner in an auctioneering firm and a pubkeeper.7

The Commission studied the pension schemes already established in NSW, Victoria and New Zealand and, in its report, recommended a means-tested pension consisting of 10 shillings per week, which would be payable at age 65. As already alluded to above, in some case, the qualifying age could be reduced to 60 where permanent incapacity was found. Like the earlier schemes, the proposed scheme was underwritten with racial exclusion and xenophobia. Recommendation 6 of the report expressly made ‘all natural-born British subjects of a white race’ eligible; however, that same recommendation expressly excluded ‘aboriginal natives of Australia, Asia, Africa and the islands of the Pacific.’8

The report is a long and comprehensive study of some 380 pages. Relevant to discussions of taxation and revenue for the purposes of modern monetary theorists are the many references throughout its pages to the possible means of funding the old-age and invalid pension through various taxation schemes, including a stamp tax and a wages tax (see, eg, page 121).9 Of some note is the fact that no federal taxation scheme was enacted in 1908, and it would not be until 1915 that the need for a federal income tax was recognised — entirely because the Great War had required increase in revenue — and introduced in the form of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1915 (Cth).

If no federal income taxation was legislated for before 1915, the questions begs: How did the federal government fund welfare for the old-aged and invalid between 1908 and 1915? The Surplus Revenue Act 1908 (Cth) gives some hints, with various taxes defined under s 4 such as ‘duties of customs paid on goods imported into a State and afterwards passing into another State for consumption’ (s 4(b)) and ‘all payments to Trust Accounts, established under the Audit Acts 1901–1906, of moneys appropriated by law for any purpose of the Commonwealth’ (s 4(d)). Of course, the specific mechanisms of early federal taxation are ripe for further examination.

Ultimately, the IOPA of 1908 incorporated most of the recommendations of the commission. Mercifully, though, it was less narrowly-focused and appeared to reject some of the moralism contained in the commission’s report. It did not, for instance, include such penalties for breaches as those used in the NSW legislation against those who supplied pensioners with alcohol. Although this had been a provision of the NSW legislation, it was not a provision of the Victorian or New Zealand schemes. These differences between jurisidctions represent the moral undercurrents, and the somewhat desultory values, that underlay welfare in Australia from its earliest inception.

https://www.findandconnect.gov.au/guide/nsw/NE0003.

https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C1908A00017.

https://www.records.nsw.gov.au/archives/collections-and-research/guides-and-indexes/infirm-destitute-asylums-guide.

Report from the Select Committee on the Benevolent Society, Sydney, 7 January 1862, Votes and Proceedings 1861-62, Vol 2, 910, cited at https://www.records.nsw.gov.au/archives/collections-and-research/guides-and-indexes/infirm-destitute-asylums-guide.

https://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/about/Pages/1890-to-1900-Towards-Federation.aspx.

https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/5013895.

https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/chapman-sir-austin-5554

https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-742931155/view?partId=nla.obj-742976407#page/n15/mode/1up/search/white.

https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-742931155/view?partId=nla.obj-743020971#page/n175/mode/1up/search/tax.